Standard 5: Culturally Responsive Teaching

Standard 5 states teacher leaders establish a

culturally inclusive climate that facilitates academic engagement and success

for all students. To accomplish an

understanding of what this standard entails, I took the class Culturally

Responsive teaching. Of all the courses

within the Teacher Leadership Program, this course addressed the most personal

and vulnerable aspects of not only my teaching, but my place in society as a

whole. Through numerous engaging group discussions, articles, and reflective

papers, I now have a better grasp as to what it takes to create a culturally

inclusive climate for students.

Reflection:

As

defined by Wlodkowski and

Ginsberg (1995), culturally responsive teaching is “a pedagogy that crosses

disciplines and cultures to engage learners while respecting their cultural

integrity. It accommodates the dynamic mix of race, ethnicity, class, gender,

region, religion, and family that contributes to every student's cultural

identity”. Prior to taking this course I

had little understanding of this definition, or even idea of culturally

responsive teaching. This is

partially due to my upbringing and background.

For essentially my entire childhood, young adult, and adult life, I have

been surrounded by predominantly white individuals. My middle school and high school settings were

mostly white, college was mostly white, and the school in which I now work is

very white. I have never been forced to confront what it means to be responsive

to other races, culturals, or norms as my world has been seen through one lens.

I have always thought of myself as tolerant, understanding, and open to people

who hold different values than me.

However this course has showed me how much more it takes to be considered

a culturally responsive teacher. I had

two main takeaways leaving this course.

The

first takeaway came during week three of the course. A required reading for the week was an

article by Gary Howard entitled, “Whites in Multicultural Education: Rethinking

Our Role”. In this article Howard calls

on all people to search for an authentic identity. Do not simplify your being into words like

“White” or “Black”, instead search deeply into your roots and find specific

details of your heritage. Not all White

or Black people are the same, even though sometimes we might lump ourselves

into one category. Howard instructs all

individuals to celebrate their specific heritage. This in turn creates more individuality and

detail in our being, instead of using blanket terms in hopes they apply to all

individuals. As stated by Howard (1996),

“Any of us who choose to look more deeply into our European roots will find

there a rich and diverse experience waiting to be discovered” (p. 336). In a response to a posting on the discussion

board forum, Eleanor beautifully stated “it is equally important for White Americans to more

deeply explore their cultural backgrounds thus enabling them to add more fully

to the rich dialogue of diversity. It's not longer a valid excuse to be

"just White" when conversing in ethnicity and culture issues and how

they impact our society.”

To apply this

concept I will seek out information regarding my specific heritage. In the past couple of years my father worked

through piecing together the Van Pelt family heritage. He is a useful resource in this journey of

discovering my true heritage and background.

With this information I can speak clearly and accurately on who I am and

where I come from. In my professional

life I can bring my culture into the classroom and the students can witness

what it means to celebrate your heritage.

As I work in a predominantly white school it is important they see what

it means to celebrate and acknowledge where we come from. In today’s time there can be a lot of white

guilt and is something I hear quite a lot in our student body. We are teaching them to acknowledge the

differences and inequality within our society, but sometimes the students

confuse this with being ashamed of who you are.

By recognizing our individual heritage we acknowledge our differences

and what makes us unique. When we are

seen as unique and individual it creates a sense of connection between all

humans. By being different, we can come together more easily. If the students acknowledge their

individuality maybe they can start to see that we are all unique and have

something to offer for the world.

The second takeaway regards the idea that

developing cultural competence is a lifelong journey. During module one, a main idea of exploration

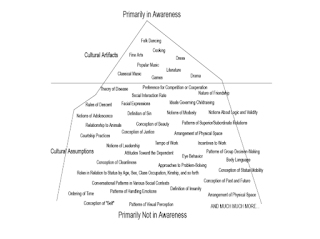

was the idea of cultural competency and what that entails. In the lecture there was a picture of an

iceberg with words associated with culture.

On the tip of iceberg were cultural artifacts, or words that most people

associate with culture. These cultural

artifacts are the low hanging fruit of understanding culture, and they are

ideas that most people use when interacting with culture. These words included, “cooking”, “games”,

“folk dancing”, and “dress” to name a few.

However underneath the surface were a plethora of other words that also

apply to culture. Some of these words

and phrases included: “nature of friendship”, “conception of beauty”, and

“definition of sin”. These words and

phrases are a main component to culture, however many people, including myself,

do not put these ideas in the front of their minds. These ideas and the image of the iceberg

taught me how important it is to take everything into account when learning

about or interacting with all people.

I will apply this

idea through openness and awareness.

Building cultural competency requires an open to mind to every aspect of

a person. As stated by Chris Lehmann

(2016), “Cultural competence means first understanding, as educational leaders,

that we come to school with our sense of who we are, and that unless we are reflective

about our own identity and how it creates a lens through which we view the

world, we will not be able to honor the identities of the students and faculty

we serve.” Nothing can be assumed and nothing can be brushed off as

“not important”. When interacting with

someone from a culture different than my own I must approach the relationship

as if I know absolutely nothing about what it means to be a human being. From this frame of mind, every action taken

or word spoken is one I must question and be curious about. Having a high sense of awareness applies to

both interactions in and outside of the classroom. As Gwenn said in one discussion posting, “As

teachers, we need to be aware and understand that our students come from

different cultural backgrounds. The more we are aware of that, the more

effectively we can communicate with our students and their families and build

relationships with them. Cultural competence can also help us build a community

within the classroom where all students feel included and safe.” We must treat our students as human beings

that need to be understood. Students

bring culture into our classrooms and we cannot expect them all to operate in

the same way. We do not teach

robots. They are individuals with

individual histories, even if those histories are only a few years old. When we interact with our students with

openness and awareness they have a space in which they can be true to

themselves and develop into their own person.

In conclusion, by

becoming a culturally responsive teacher, I am simply becoming a better teacher

who is more aware of the students and their individual needs. Often, teachers are instructed to meet the

needs of their students. However most of the time we forget to account for

cultural needs, usually because we are unaware of what these needs might

be. It isn’t always about learning

styles or academic ability. Learning,

understanding, and respecting every student’s heritage and cultural background

is highly important if we want to connect with them and ensure academic

success.

Artifacts:

Autobiography

Sources

Howard, G (1996).

Whites in multicultural education: Rethinking our role. In J. Banks (Ed.), Multicultural Education, Transformative

Knowledge and Action (pp. 323-334). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Wlodkowski, R., & Ginsberg, M. (1995). A

Framework for Culturally Responsive Teaching. Educational Leadership, 53(1). Retreived from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/sept95/vol53/num01/A-Framework-for-Culturally-Responsive-Teaching.aspx

Lehmann, C. (2016). How Leaders Can Improve Their

Schools’ Cultural Competence. Retrieved from

Comments

Post a Comment